The Library: Yugoslavia, My Fatherland by Goran Vojnović

/Read by: Paul Scraton

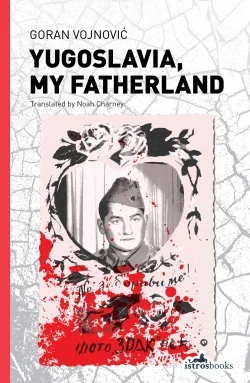

In the departure lounge of Ljubljana airport, two hours early for our flight back to Germany, I pulled a book out of my bag and start to read. Two flights and about five hours later I read the final page as the plane made the final approach to Berlin’s Tegel Airport. I had crossed the Alps and the heart of Germany, but really I had been in the countries of the former Yugoslavia, as explored through the eyes of a narrator who has discovered, sixteen years after he believed his father was dead, that in fact that this barely remembered man who was an officer in the Yugoslav People’s Army is actually alive and living in hiding, a fugitive of the Hague as a wanted war criminal. Yugoslavia, My Fatherland by Goran Vojnović tells the story of the narrator’s journey to find his father, a journey that causes him to reflect on how the disintegration of his family is tied to the disintegration of the country, and the world, that they used to call home.

I came to this book by coincidence – the man sitting next to me on my flight out to Ljubljana a week earlier was reading (in Slovenian) a book by Goran Vojnović who was then profiled (in English) in a magazine I picked up at the airport, waiting for my bags to appear. I have long been interested in the history of the former Yugoslavia; ever since I was a student in Leeds starting out my degree only two years after the Dayton Peace Accords had brought to an end the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina that had played out on our teatime television screens throughout my teenage years. Reading about Yugoslavia, My Fatherland in the magazine was what led me to a book described by the English publishers as a work that “deals intimately with the tragic fates of the people who managed to avoid the bombs, but were unable to escape the war.”

Goran Vojnović was born in Slovenia in 1980 and is a well-respected director and screenwriter as well as being a bestselling novelist. I would love to speak to him at some point about how much of the background of his protagonist – school experiences in Ljubljana in the 1990s for instance – reflect his own, as the power of this novel is in how Vojnović manages to explore the break-up of Yugoslavia from the multitude of perspectives in the different parts of the former Federal Republic, allowing all voices to have their say without, it seems to me, judgement or bias one way or the other. One of the finest scenes in the book is when his new classmate in Ljubljana, where the teenage narrator has moved with his mother from Pula, Croatia via Belgrade and Novi Sad, explains what is happening in Yugoslavia via the nationalities of the other children in the class.

Throughout the book the narrator remembers the slow collapse of the world of his childhood through remembered scenes in apartments, the tone of the newsreaders on the evening television and the atmosphere in Ljubljana where he lives but never quite feels at home. The other strand of the story is of course the present-day search for his father, and the impact of the knowledge of the crimes he is alleged to have committed in a village in Slavonia. The story is told in a matter-of-fact, sometimes humorous tone, and Vojnović certainly has a flair for set-piece scenes, both in the description and the dialogue, but what is most impressive is how the battle of ideas that reflects battles taking place elsewhere in real life, and the complexity of personal identities both in the time of the disintegration of Yugoslavia and today, are told through the multitude of characters who appear in the book. This is impressive writing, and one of the best tellings of the Yugoslavia story that I have read.

This is a novel about place, about memory, and about how the world of our childhood can be destroyed so that it no longer exists, even if it remains a name on a map. Along the way it deals with a number of signifiers of home and belonging, from the behaviour of guests at a wedding to the differences in language, not only between the Slovene his mother insists on using when they move to Ljubljana and the Serbo-Croatian that has been the family language up to that point, but the differences within the latter, when his Bosnian classmates make fun of the narrator as he speaks the Italian-tinged version of his childhood home on the coast.

Goran Vojnović tells this story in relatively straightforward language, but the more you read the more you realise how complex the novel is as it creates this portrait of a disintegrating country through the personal story of a disintegrating family. It is a reminder of the power of literature, and of fiction, to help us come to the essential truth of history and its impact on people. Much credit must go to the translator Noah Charney and the publishers Istros Books for bringing it to an English-speaking audience as this is an important and powerful book, and one which deserves to be read as widely as possible.

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland by Goran Vojnović, translated by Noah Charney, is available via the publishers, Istros Books.