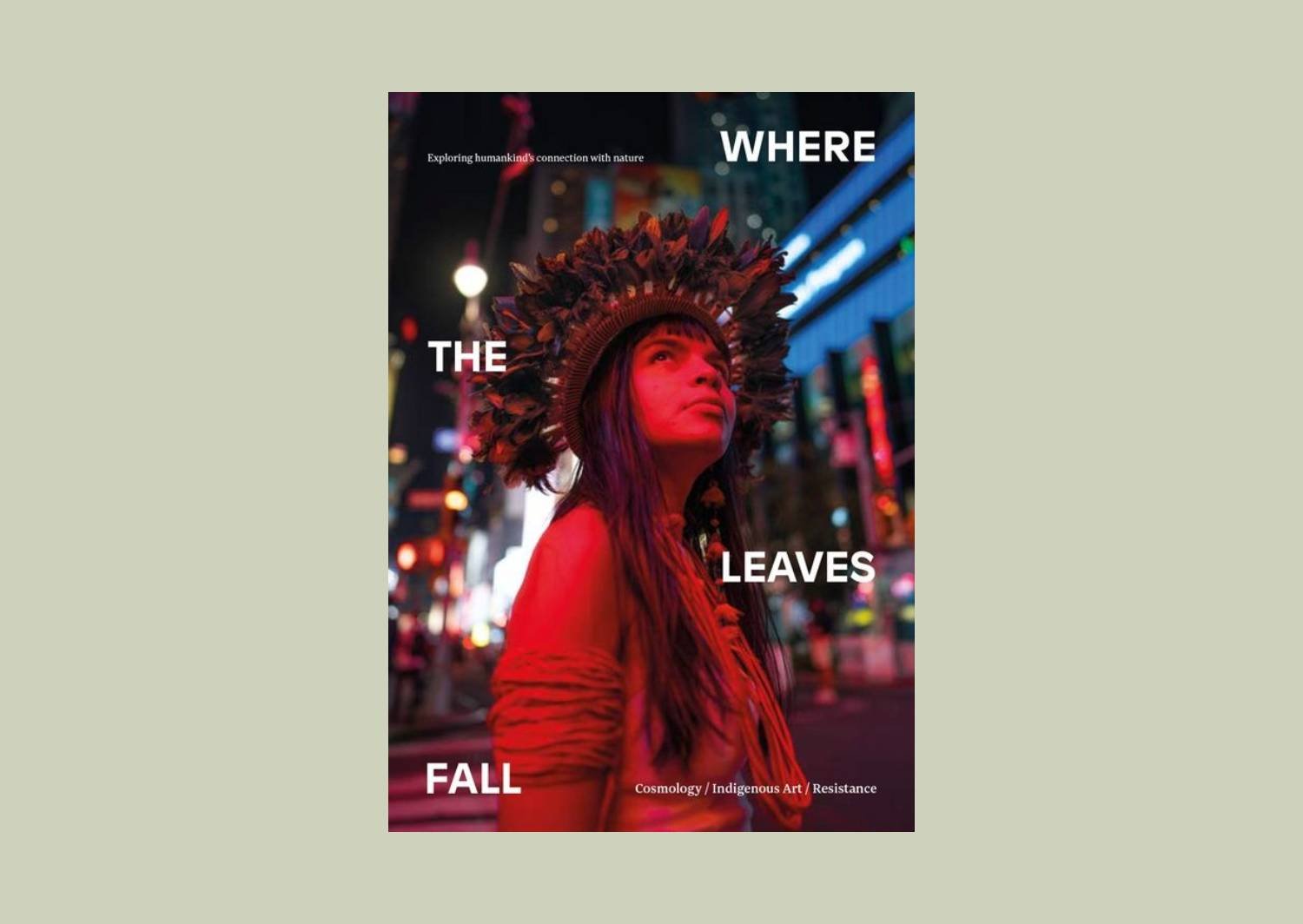

Printed Matters: Where the Leaves Fall

/IMAGE COURTESY OF WHERE THE LEAVES FALL

By Sara Bellini

“Indigenous thinking breaks the extractive capitalist rationalism that looks at nature the same way it looks at other people, aiming to dominate them. When looking at nature with a holistic sense, we understand that we are part of it and that we are connected to this planet.”

These words are taken from the editor’s note of Issue 12 of Where the Leaves Fall, entirely guest-edited by Indigenous activist Txai Suruí. The magazine regularly gives space to activists and Indigenous people from all over the world to share their experiences and their view of a sustainable future.

Where the Leaves Fall aims at exploring “humankind's connection with nature”, through articles, interviews, illustration and photography on the themes of art, agriculture, technology, science, philosophy, human rights and any field where our impact on the planet is visible. The commitment to rekindling our relationship with nature goes beyond articles on how climate change is linked with social justice. The entire production process of the physical journal is sustainable, from minimised paper waste to chemical free ink and a wormery to finish the staff food at the printing facility.

The contributors to the journal are diverse, including marginalised voices from the global south, Indigenous people, women, people of colour and people from the LGBTQI+ community. Community, at a local as well as a global level, is fundamental to reach a more balanced relationship with the world we share. Where the Leaves Fall was born out of this shared value at OmVed Gardens, a space in north London - partnered with the UN World Food Program - promoting ecology and agricultural sustainability, where people can engage with and experience nature in creative ways.

Below you’ll find our interview with editors Luciane Pisani and David Reeve.

Image courtesy of Where the leaves Fall

Why did you choose the print magazine as a format?

At the time we started there weren’t many magazines looking at climate breakdown through the lens of our connection with nature and print felt like a good way to take people away from digital spaces – including social media. We were very careful in how the magazine is printed – printing with one of the most environmentally friendly printers in the world - if you smell the magazine you won’t catch the whiff of any chemicals.

However with the pandemic and the various lockdowns and restrictions around that it became apparent we needed to go online as well. So we now encompass physical spaces for events, print, and online. One of our Australian collaborators recently told us our magazine is a message stick – you can look that up.

One of the focuses of WtLF is climate change. How do you turn feelings of anxiety, anger and hopelessness into a force for change?

It’s difficult to feel hope at a time of climate and societal breakdown. Systems that have held us up for so long are slowly collapsing and that’s creating a lot of discontent. Capitalism has failed us and the planet and we’re now in a system where politicians and industries are desperately trying to hold on to what they had and many people are being cast adrift. The growth of the far-right is a result of this. With the UK government’s indifference, the National Trust RSPB and WWF came together to create the People’s Plan for Nature to engage the public in caring and connecting with the natural world.

Similarly the UK government is largely ignoring the National Food Strategy that it commissioned so there’s a movement towards how people and business can take action and affect change. Rob Hopkins came up with the Transition Network (you can read an interview with Rob in the mag) which is all about communities coming together and reimagining the future. In Brazil you have movements such as the Cozinha Ocupação 9 de Julho and MST (Landless Workers’ Movement). Where governments and corporations fail us, people can come together and affect change - it’s about demonstrating that things can be done differently and work.

What’s the importance of community and connection for you?

Our focus is on growing our local and global communities. Community is everything. It’s diversity. It’s understanding. It’s collaboration. It’s imagination. It’s strength. It’s power.

Could you share some details about your creative process, for example in regards to finding themes and selecting submissions?

The magazine is a project of OmVed Gardens – a space in north London that has undergone ecological transformation. We meet up there to discuss the things that people might want to focus on or talk about. From these meetings come the magazine’s themes. We then meet again to discuss initial ideas around those themes before casting the net out to our global audience. We have a period of submissions and then from the ideas developed at OmVed and the varying submissions, we select the features (text and photographic) and dialogues (shorter essays) for the mag.

For the 12th issue we wanted to do something different. Everyone was largely disappointed by the results of COP26. We watched the opening ceremony with some really impressive speeches – but were the ears in the auditorium listening? One of the speakers was Txai Suruí – an Indigenous activist from the Amazon’s Paiter Suruí people. In the lead up to COP27 we were interested in what the magazine would be if we asked Txai to edit the magazine, bringing her perspective to our readers at this crucial moment in the climate emergency.

We wanted to step back and allow her complete ownership of the editorial direction, and it has led to a series of fascinating features from the perspective of Indigenous peoples – mostly from the Amazon but also other parts of South America. As Txai said: “For a long time, the stories written about the Indigenous peoples of Brazil and the world were told through the eyes of the coloniser, almost always stereotyped and from a perspective of domination and superiority,” she writes. “We are now protagonists of our own history and the narrators of it - a history that didn’t start with the invasion. We continue our resistance that has lasted more than 500 years and that does not end now.”

It’s a powerful issue. As the shaman Davi Kopenawa states in the issue – we, the westerners, are the earth eaters. Our relationship with the land is one of extraction and destruction. It’s not about us saving Indigenous peoples but recognising that we need to open up and that they are the ones who can actually save us. They are amazing storytellers, artists and experts in conservation. They have a deep connection with the land and have survived and developed alongside it for 1000s of years.

What did you learn about humankind’s connection with nature since issue 1?

We are nature and a part of the ecosystems in which we live. The rivers and seas run through our bodies. Our family includes the flora and fauna around us and the living soil under our feet.

Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you’d like to share with our readers?

If you’d like to know more about the magazine or become a part of the conversation then you can sign up to our newsletters, follow us on Instagram and check out the mag.