Printed Matters: Point.51

/By Sara Bellini

The 51st parallel north is the point where continental Europe and the UK meet, halfway between Dover and Calais in the English Channel. This meeting point also inspired the name of Point.51, a London-based magazine of slow journalism and documentary photography.

The look is simple and effective: a red matte cover, a full-page portrait, one word that identifies the theme of the issue and a phrase to invite you in. The content requires time, a comfortable armchair and a cup of tea: Don’t flip through the pages, linger, take everything in. This is what I immediately loved about this new publication, the slow and in-depth approach to stories, narrated equally through words and images.

We all consume the news, or more often than not, news headlines, and their abundance and speed detach us from the content and from the people the headlines are about. Point.51 gives you the opportunity to explore significant news topics through personal stories, focusing on ordinary people and how they relate to the bigger narratives of our multi-layered present. It gives you time to empathise, reflect and form an informed opinion, which is crucial in shaping contemporary conversations.

Issue 4 will hit the shelves in May, and meanwhile we caught up with editor Rob Pinney:

What was the inspiration behind Point.51 and what drives you?

We wanted to do something that gave us the space and time to really dig into complex stories – both in the writing and in the photography – without having to strip them down. We want to work on stories that challenge us, and challenge our readers, and I think that curiosity is really what drives Point.51 forward.

Why did you choose the print magazine as a format?

I think we knew that Point.51 was going to be a print magazine from the outset. In fact, I don't think I can remember us having a conversation about the possibility of doing it any other way. But as we've grown, I think it's now clearer than ever that print is the right format for us.

I like to think about it by flipping the question on its head: how would we want to read these stories? For me, it is undoubtedly in print. I want to sit with them and read them through, following the story as it unfolds, without distractions.

Point.51 comes out twice a year, and so the stories we work on for the magazine are usually put together over fairly long periods of time. They're designed to last – we want them to feel just as relevant in five years time as they do today – and there's a permanence to pulling them together in a printed magazine that reflects that.

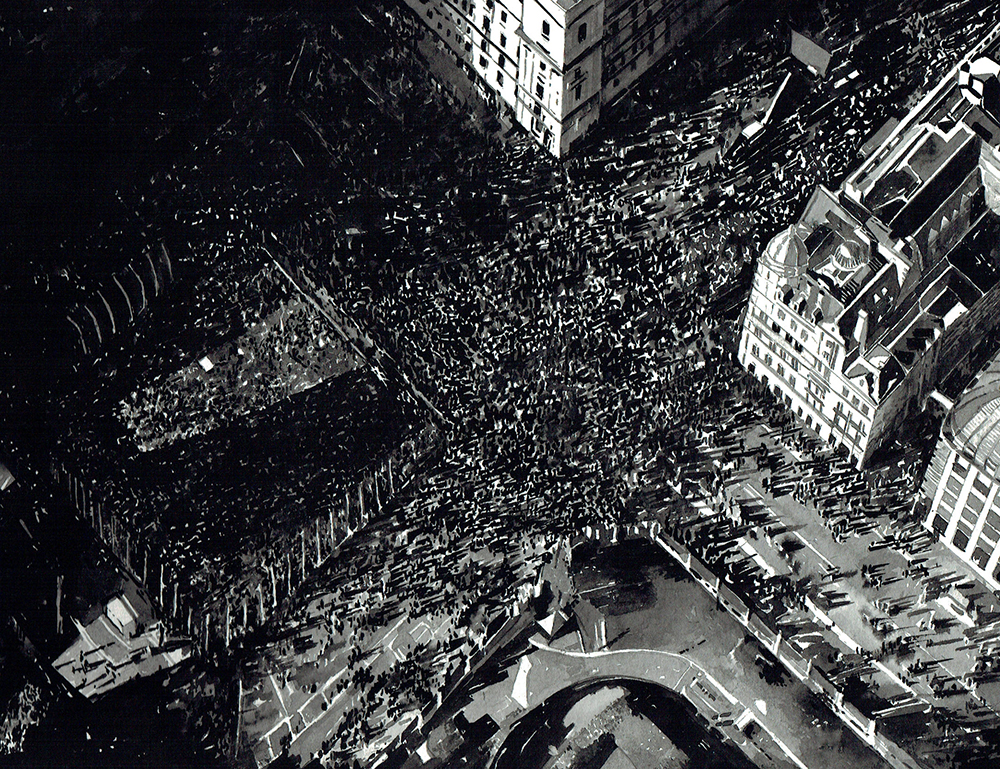

Then it's also important for the photography. My background is as a photographer, and we pride ourselves on commissioning and publishing really great documentary photography that stands shoulder-to-shoulder with our journalism. There are 102 images in our latest issue, and without wanting to sound too old fashioned, I think that work really is at its best when seen in print.

At the core of your magazine are a strong sense of place and a genuine interest in people, what’s the relationship between these two elements?

Definitely. Both people and place are essential to the stories we work on. But they come up in different ways, and I think the relationship between them changes from story to story.

People are at the forefront of all of our stories – that has been a constant throughout. But place comes up in different ways. To give a couple of examples: there is a story in our first issue about Cuban asylum seekers arriving in Serbia to make use of visa-free entry for Cuban passport holders, which exists as a legacy of the Cold War. In that case, place plays a very specific and explicit role in the story. Then there's a story in our second issue about Port Talbot, an industrial town in north Wales known for steel production. When the steelworks opened there in the 1950s, it employed 18,000 people – literally half the town – but today that number has fallen to just 4,000. At the centre of the story are multiple generations of a family with a long-standing connection to the steelworks, and you get to see how those different generations – with different experiences – relate to their town. Bringing those different perspectives into our stories is really important.

So I don't think you can say that there's a fixed or static relationship between people and place in the magazine, but the stories are definitely concerned with the way the two inform and shape each other.

How has Point.51 changed since Issue 1 and what are your plans for Issue 4?

When we started out, lots of friends and colleagues thought we were crazy trying to start a print magazine for long-form journalism and documentary photography when other publications were disappearing left, right, and centre. They were probably right – it's certainly not easy. But we've seen the magazine go from being just an idea to an established title with a solid and growing reputation.

Issue 4 is well underway, and should hit the shelves in May. The theme for the next issue is Nations and Nationalism, but as with all of our issues, we're coming at it from a variety of angles – from the story of a "micronation" in Italy to the relationship between people living in Gibraltar and La Linea de Concepción, the towns on either side of the border.

The team of people working on Point.51 has also grown – Nick, Sara, and Meg have joined us, and their knowledge and hard work is already showing. So yes, there have been lots of changes.

But I also think that, in a fairly fundamental way, it hasn't changed at all. We had a very clear idea of what we wanted Point.51 to be when we started it: a straightforward magazine for considered long-form journalism and original photography. I think we've stuck to that pretty doggedly, and I think it's what a lot of our readers really like about it.

Can you tell us a bit more about the concept of little story/big story behind Point.51?

Yes certainly! "Big story/little story" is an approach we use when working on stories for Point.51. We can't claim it as an original concept – it has been put to use (and written about) widely – but it's something we try to put into practice wherever possible.

Essentially it comes down to the choice between doing something that is wide but shallow or narrow but deep, and deciding where you think the real value is. The stories we like to work on for Point.51 are usually concerned with pretty big topics: we've reported stories about migration and asylum, the climate crisis, mental health, Brexit, and the Irish border, to name a few. But in each case we're zooming right in to tell a smaller story within that, concentrating on just a few individuals, or a single place, or maybe both.

The small stories are the ones we can really relate to, and that stay with us. And I think that if you tell the small story really well – bringing in all the detail and complexity that exists in real life, and which often gets cut out – then you're also providing a much richer perspective on the big story too.

We're not trying to tell readers what to think or to persuade them to see something in a particular way. We want to bring people great stories that are told thoroughly and faithfully, but ultimately it's for them to engage with them on their own terms.

As usual, Berliners can find Point.51 at do you read me?!? and Rosa Wolf. Check out the website for online shopping and a free newsletter with more articles and photography.