Back inside the forest cover, the track splits around a stubborn old hornbeam, its knotted roots securely encased under the top layer shingle. The route to Mill Plain is kinder here, on the west side of the A104, where there’s no need to engage with the fractured grimness of the Waterworks Corner pedestrian interchange. This is where the path breaks clear of the cover and ramps up, knobbly, cracked, onto a raised, open ridge, where the track bends gently through the long grass and willowherb. To the right is the Thames Water pumping station, its wonky rear steel fence offering negligible protection from anything with sufficient stature and determination, and the Waterworks Corner roundabout, only metres away. South Woodford to Redbridge, Barking, Beckton, Woodford Green, Loughton, Epping. To the left, the scoop of the Lea Valley. The atmosphere is sleepy and strange, ominously peaceful. Twin paths converge and slope down towards Forest Road, the occasional tent visible through the bushes, and the sharp tops of City of London buildings poke through the trees. Look into the valley-dip from the bridge adjacent and it’s Walthamstow, Tottenham Hale, Edmonton, Harringay, Alexandra Palace, Brent Cross. Stadiums, reservoirs, retail parks, antennae, the ever-present wash of the traffic, distant and interior.

On the other side, nestled behind the roundabout, is a raised, circular grass platform, flat, wide, and empty, aside from a shabby Thames Water brick hut at the edge. Marked, appropriately, as “The Circle” on Google Maps, it offers readymade laps for joggers, and numerous exits, down the tight, surrounding verge, back into the cover of the forest. Manmade and incongruent, barely visible from the road, it’s easily cast as the site for something more atavistic and obscure. A sacred place, where anonymous figures gather to offer up euphoric human sacrifices to a provincial woodland deity. A landing site for a small extra-terrestrial reconnaissance craft, carved out to order by devoted earthbound aides. A place to hide in the open. Stay too long and the joggers, smiling and efficient, assume – possibly through no fault of their own - a slightly sinister, collective aspect.

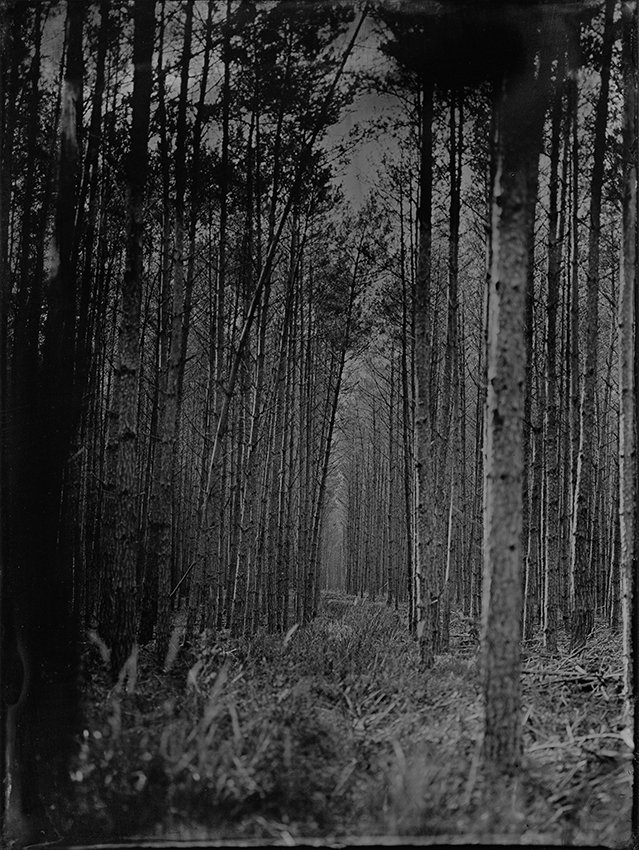

The path to the bridge over the A406, just beyond, is gravelly and uneven, bricks and slate pieces baked into the dirt, recalling the clay pits and brick kiln once residing nearby. A well-covered passage, accessible via a tight, cosy glade, runs parallel with the road, overlooking it. Thorny and narrow, discarded carrier bags hanging forlornly from bushes, a person-thin viewing corridor for the unending, thrusting snake of the daylight Walthamstow traffic. Crossing the bridge, to the South Woodford side, is a journey of metres but feels like an escape from this exhaust-choked claustrophobia into something wholesome, time-frozen, pastoral. The trackway widens, getting flatter and kinder underfoot. The canopy is less oppressive, offering a pleasing combination of light and shade. Patches of sunlight cast through the trees, dappling the floor. Little private clearings just off the main track lead into exquisite mini-mazes. To the left, an intricate branch structure built around a large horizontal trunk, and a carved stone memorial marking the birth site of a celebrated gypsy evangelist. Everything honeyed in yellows and browns. With minimal effort, you can block out the vehicle drone. Approaching the open field in front of Oak Hill, boundaries begin to dissolve; thoughts flicker and fade, hazy before they have fully formed. You start to feel drowsy, detached, separate, before the sudden rustle-rush of a small animal brings you back, sharply, to jittery alertness. You turn and hurry back the way you came. The sun hangs low and follows you, blinking and glinting through the gaps, and the temperature starts to drop.

***

Dan Carney is a musician and writer from north-east London. He has released two albums as Astronauts via the Lo Recordings label, and also works as a composer/producer of music for TV and film. His work has been heard on a range of television networks, including BBC, ITV, Channel 4, HBO, Sky, and Discovery. He also has a PhD in developmental psychology, and has authored a number of academic research papers on cognitive processing in genetic syndromes and special skills in autism. His other interests include walking, writing, and spending far too much time thinking about Tottenham Hotspur. Dan on Twitter.